From Basel I to Basel III – Overview of the Journey (Basel 1, 2, 2.5 and 3)

In the beginning, the international Basel Committee on Bank Supervision (BCBS) created Basel I, a series of regulatory guidelines for the banking sector that outlined specific measures that aimed to reduce institutional credit risk.

The Basel I Capital Accord of 1988 set forth minimum capital requirements for major financial institutions. Over the next several years, financial environments across the globe evolved. Newer financial institutions came into existence. More innovative products and services were introduced.

And the nature of financial risks started changing. The international Basel Committee on Bank Supervision saw this as a signal for Basel I to evolve as well, and in 2004 it came up with Basel II – a series of rules to address the post-1988 financial climate.

Basel II was adopted by the EU in January 2008, while its implementation was delayed until January 2009 in the US.

Subsequently, there were even more glacial changes in the global financial environment, which lead to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09.

The international Basel Committee on Bank Supervision and other sovereign regulators recognized how much risk, to individual countries and world financial markets, a single bank’s operations could get.

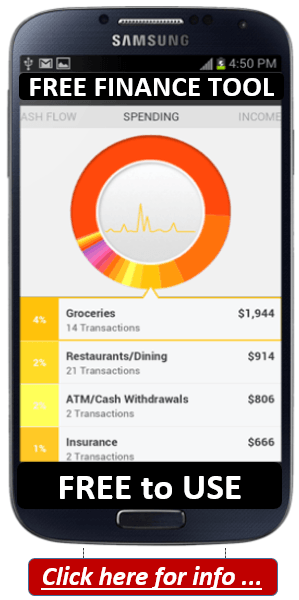

Image Source: KMPG Analysis of BCBS

Ultimately, they realized that a more comprehensive overhaul of the Basel II protocols was needed.

However in the interim, until more complex negotiations for a major update were scheduled, BCBS released Basel 2.5 in July 2009 to address the growing concern over banks’ capital requirements, particularly with respect to riskier credit-related products.

After a series of protracted negotiations, the international financial community agreed to tighter monetary and fiscal reforms for the financial sector. These regulations, which were agreed to in July 2010, were finally endorsed as “Basel III” in September 2010, addressing Basel II shortcomings as related to Regulatory Capital and Additional Risks.

The Basal Committee – Brief History

To understand what makes protocols like Basel so important to us, we need to take a brief look at how Basel came into being in the first place.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was created in 1929-30 to act as a global entity to foster world-wide financial and monetary collaboration, and to act as banker to central banks.

But by the end of the Second World War, institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were established under the Brenton Wood system of July 1944, and the BIS was deemed to be irrelevant (NOTE: Though the Brenton Wood system failed, The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) still exists today).

During the late 1960s and early 1970s the Brenton Wood system (based on fixed exchange rates) started unravelling.

The June 1974 suspension of the banking license of Bankhaus Herstatt (German bank), and the October 1974 closing of Franklin National Bank of New York due to massive foreign exchange losses, was a wake-up call for G-10 nations to take a fresh look at disruptions to international financial markets.

In January of 1975, G-10 central bank governors met in Basel, Switzerland, and established a Committee on Banking Regulations and Supervisory Practices to enhance cooperation on banking supervisory challenges, and to exchange know-how on improved banking supervision globally.

The Committee aims to meet its mission by:

- setting minimum supervisory standards

- improving the effectiveness of techniques for supervising international banking business; and

- exchanging information on national supervisory arrangements.

The group was later renamed to “Basel Committee on Banking Supervision” or BCBS in recognition of the town where it was first conceived, and is comprised of nearly 27 regulatory bodies from countries around the globe.

Why One Basel Led to Another

The Basel Committee has two main reasons for proposing its Basel framework:

- to strengthen international banking by boosting their capital requirements

- to remove inter-country competitive inequalities amongst G-10 banking institutions

When Basel I was effected back in 1988, the world was a rather simple place to conduct financial transactions.

And though Basel I was a simplistic effort to regulate the financial marketplace, it did bear fruit. Banks, which were previously undercapitalized, responded by improving their capital ratios in order to comply with Basel I.

In 1988, the average ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets of key banks in the G-10 stood at 9.3%. By 1996, this rate had gone up to 11.2%.

More importantly though, Basel I introduced a standardized definition of capital adequacy globally, and heightened awareness of prudent capital management across the financial industry.

All-in-One Change Management Tools

Top Rated Toolkit for Change Managers.

Get Your Change Management Tool Today...

Basel 2 & 2.5 (Basel II & II.5) Enters the Stage

But along with the good came the bad, and financial experts were quick to see through the loopholes and deficiencies in Basel I.

While they acted in line with the letter of the framework, their actions were far from the spirit in which Basel I was enacted.

The simplicity of the protocol gave rapid rise to ingenious (and devious) products and services (such as selling of Credit Swaps by insurance companies) that circumvented some of the more stringent Basel I rules.

Critics felt that something more than just Capital Ratios was needed to assess the true risk potential of a bank.

And while Basel I focused on key financial risk metrics, it completely ignored the need for a robust risk management process. Enter Basel 2 (II).

Basel II, initially, as well as subsequently through enhancements under Basel 2.5, took a much broader view of risks in the financial industry such as:

- its scope was applicable to international banking on a consolidated basis (as opposed to a limited country or regional view)

- it excluded insurance activity from the purview of “financial activity”

- it set aside a banks’ investments in other commercial entities while calculating risk thresholds

The 3 Pillars

Basel II broadened the focus of risk assessment and management by enforcing a 3-pillar approach in the capital accord, these included:

- Pillar 1: Minimum Capital Requirements. Banks were required to maintain a designated acceptable capital level. It also enhanced its approach to assessing both Credit and Operational Risks.

- Pillar 2: Supervisory Review Process. Banks were required to assess their solvency in light of their risk profile. Additional supervisory oversight was introduced on how banks calculated their capital requirements, and regulators are now able to intervene well before those capital levels start to deteriorate.

- Pillar 3: Market Discipline. This pillar enforces enhanced levels of disclosures by the bank, especially around their risk profiles, their capital structures, their risk management and measurement practices, and their capital adequacy.

Subsequently, Basel II was further fortified, albeit as a temporary measure until a more robust (Basel 3) accord was reached. With the introduction of the Basel 2.5 enhancements to Basel 2, several shortcomings in the Basel 2 framework were addressed.

However, the fundamental guiding principles of the 3 pillars remain largely intact.

Basel 2.5 does, however, introduced tougher regulations that mandated banks to hold larger amounts of capital against the market risks they ran in their trading operations.

The 4 major enhancements to Basel II, as delivered in Basel II.5, include:

- a deviation from a Value At Risk (VaR) -based capital requirement of Basel II, into a Stressed Value At Risk (SVaR) model through Basel II.5

- an attempt at capturing credit margin and default risks by introducing the Incremental Risk Charge (IRC)

- a set of new charges for securitization/re-securitization of banks’ positions

- introduction of a new measure to correlate trading positions, known as the Comprehensive Risk Measure (CRM), which assesses the underlying exposures for default and migration risks

In general, these new enhancements in Basel 2.5 only enhanced the measures already enforced via Basel II.

According to Standards & Poor’s research:

“The new regulatory measures are already significantly increasing capital charges on traded risks, particularly for large international banks”

which should further help de-risk existing capital markets by discouraging risky behavior.

Basel II and the 2008-09 Meltdown

Basel 2, and its associated Basel 2.5 enhancements, were harshly criticized for not doing enough to stave off the financial crisis of 2008.

It was felt that the average levels of capital requirements enforced were inadequate, and that the assessment of credit risks was improperly delegated to inappropriate (non-banking) institutions.

Furthermore, Basel II and Basel II.5 were criticized for making assumptions that the internal models used by banks, to measure risk exposure, were superior to those which external (supervisory) agencies could have implemented.

The framework was also seen as providing an incentive to banking intermediaries to “hide” (deconsolidate) risky exposures from the banks’ balance sheets.

Time for a New Basel – Basel 3

In wake of the 2008 financial meltdown, despite implementation of Basel II and Basel II.5, the Basel Committee decided that more needed to be done to foster transparency and accountability within international banking. The Committee felt that, to fend off another similar crisis, amongst other steps, more supervision and control was needed over how banks reported “Tier 1” capital.

Basel 3 set itself three major aims:

- to make participating banks strong enough to withstand future financial shocks (similar to the 2008/09 crises) without causing contagion to other economies/sectors

- to enforce greater risk management within all aspects (including operational) of the financial industry

- to strengthen the financial industries’ transparency, governance, and disclosure practices

Under Basel 3, banks would be mandated to maintain healthier amounts of “true” capital.

The way that the Committee did this was to have banks exclude the use of Preferred Equity and other hybrid capital instruments from the calculation of “Tier 1” capital reserves.

Other areas, that Basel III focused on include:

- stress testing

- practices governing “fair value” assessment

- executive compensation/remuneration practices

- stronger corporate governance

- scrutiny over “large exposures”

- increased oversight of “concentration risk”

While some of these protocols existed in previous Basel accords, they have been updated and strengthened in Basel III.

Others, like stress testing requirements, are not new and are in direct response to the 2008 crisis.

When the initial Basel III guidelines were published in 2010, the world (especially regulators, investors, and consumers of financial products and services) waited in great anticipation for its January 2013 implementation.

However, industry lobby groups and other parties-at-interest (and at “disinterest”) continued to make representations to the Basel Committee for updates and changes to the accord.

US banking lobbyists pushed back hard to have the liquidity restrictions on its members relaxed.

They contended that in the three years since the initial draft was published, most US banks had already done a lot to improve their liquidity (Tier 1 capital) ratios – even before Basel III implementation kicked in.

However, observers were quick to point out that was not the case. They pointed out that:

“American banks were only able to raise their holdings of liquid assets by $700bn, less than half the $1.5trn identified as target at the end of 2010.”

When January 2013 finally rolled around, the Basel Committee released a newly-updated accord, which observers felt had “…watered-down some of its most important requirements…“

To the disappointment of many a financial watchdog, the implementation timelines of Basel III, as envisioned in the original draft, were also significantly relaxed in the final version of the proposal.

Critics of Basel III believe that this third kick at the can is doomed to fail, just as the previous two-and-a-half kicks have failed.

And one key reason why this could happen is because of how Basel III deals with the calculation of risk. In the words of one critic:

“The most serious failure in Basel III is that it doesn’t address the principal contribution of Basel II to the last financial crisis, namely, the calculation of risk-weights.

Because it doesn’t really change the risk-weighting, Basel III doesn’t force banks to increase the amount of capital they must hold against some of the higher-risk assets they do hold. In that sense, Basel III simply reinforces Basel II – under whose watch the 2008 crises took place.

Overall however, both Basel 2.5 and Basel 3 have:

- made it costlier for banks to indulge in riskier behavior

- made it more difficult (due to new oversight and stringent restrictions) for financial institutions to take unwanted risks

- provided a more robust early-warning system to detect and prevent many financial disasters from happening

What to Expect

The full implementation of Basel III is not likely to be finalized (globally) until 2019, subject to local (country-specific) phase-in requirements.

For instance, based on a report from the Congressional Research Service, the implementation of key Basel III framework proposals in the US were harmonized to work in tandem with other U.S legislation, specifically the Dodd-Frank Act.

Given how interconnected today’s global financial institutions are, and how quickly “contagion” from one country can spread to another’s financial system, a lot could happen between now and 2019.

As the milestone dates for implementing key Basel III proposals tick by, the Basel Committee will continue to monitor its implementation, through its Regulatory Consistency Assessment Program (RCAP), as will other member, central bankers.

It is very conceivable that, in the event of yet another financial crisis of major proportion, the world could very well see a Basel III.5 come forth from the Basel Committee.

The Journey in Summary

Basel I was a rather simplistic, first significant attempt, in a post-World War era, of reigning in the potential of large banking/financial institutions from causing chaos to global economies. Basel II, which was released in 2004, used a 3-pillar approach to enhance risk measurement and assess operational risks of those financial institutions.

With Basel II.5 enhancements in 2009, came even greater measurements of risks with respect to securitization, as well as more oversight on a bank’s trading book exposures.

The most recent Basel accord (III), agreed in December 2010, sets about introducing a new global liquidity framework.

Basel 3 was altered in November 2011, January 2013, and January 2014, to address several concerns that member states and business representation bodies raised.

While Basel 3 has already started to be implemented, various aspects of the new accord will be subject to “transitional and phase-in arrangements.”

As the Basel accord currently stands, full implementation is not scheduled to occur until January 2019.

AdvisoryHQ (AHQ) Disclaimer:

Reasonable efforts have been made by AdvisoryHQ to present accurate information, however all info is presented without warranty. Review AdvisoryHQ’s Terms for details. Also review each firm’s site for the most updated data, rates and info.

Note: Firms and products, including the one(s) reviewed above, may be AdvisoryHQ's affiliates. Click to view AdvisoryHQ's advertiser disclosures.