DODD FRANK SUMMARY – BACKGROUND

During the fall of 2008, the so-called “best of times” started catching up with those that lived it.

America faced a financial crisis of epic proportion that resulted in millions of lost jobs, and trillions of dollars in lost personal and corporate wealth.

The cause was a financial environment that:

- was antiquated and fragmented

- faced a broken regulatory system

- had little or no oversight

- relied excessively on fine print and hidden fees

The immediate result of living the “best of times” to their fullest, totally unchecked and barely regulated, was a slew of failed corporations and financial institutions.

There was a liquidity crisis that was so severe that financial institutions refused to lend to each other, lest the borrowing institution defaulted on their obligations.

Corporate creditors and ordinary borrowers found it extremely difficult to secure financing and lines of credit from banks and mortgage companies.

To immediately halt a ripple effect from destabilizing the country’s entire economy, Congress passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA) which, through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) enacted on Oct. 3, 2008, empowered the Treasury to acquire up to $700 billion of mortgage-backed securities and a variety of other assets from a number of “troubled” institutions.

This was a time when, amongst other high-profile activities:

- Lehman Brothers went bust, and had to seek Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection

- JP Morgan Chase took over control of the failing Bear Sterns

- American International Group (AIG) lending division was “bailed out” using Federal funding

- AIG’s credit default swap division received bailout funding

- Companies such as General Motors and Citigroup needed use of TARP funds for bail out

- The Federal government engineered the takeover of troubled mortgage lenders Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae

The primary objective of TARP was to prevent contagion of the crisis by injecting funds to restore liquidity into the financial markets.

Unless something like TARP was implemented quickly, confidence (domestic and international) in America’s financial institutions could wane, ultimately leading to even deeper, unresolved issues.

THE BIRTH OF DODD-FRANK

While the 2008 initiatives, such as the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and TARP, were reactive responses to deal with an ever-deepening financial crisis, they were by no means considered comprehensive enough to prevent the same situation from repeating itself.

A more systemic review of the crisis revealed that far deeper reform of the entire financial system was needed to address the underlying causes of the 2008 crisis.

Image Source: Pixabay

On March 15, 2010, Senator Christopher J. Dodd (D-CT) introduced a bill in the Senate, which was passed approximately two months later, on May 20. U.S. Representative Barney Frank (D-MA) revised the bill, which then received House approval on June 30, 2010.

In tribute to the efforts of these two lawmakers to reform the ailing financial industry, the bill was named the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act.

The Act became law on July 21, 2010, when President Obama signed and made it the law of the land.

DODD-FRANK IN SUMMARY

The Dodd-Frank Act has been dubbed the “Wall Street Reform Act.” In simple terms, it:

- introduces greater supervision and oversight of financial institutions

- provides a formal framework for dealing with financial companies that may be “too big to fail”

- introduces stricter regulations around capital requirements for banks and other lending agencies

- enforces stringent regulation of over the counter (OTC) derivatives

- creates a new agency tasked with governing consumer finance and protecting retail customers of financial institutions (banks, insurance companies, mortgage brokers, credit card companies)

- regulates credit rating agencies (such as Standard & Poors, Moody’s and Fitch)

- introduces tighter control and transparency over corporate governance, specifically with respect to executive compensation

- bars banking institutions from involvement in specific investment activities, while limiting their relationship with hedge funds

- mandates certain private fund advisory companies to provide additional disclosures about their relationships with clients, while also requiring them to register with the government

As indicated above, this is a “simplistic” Dodd-Frank Act summary.

Buried within the Dodd Frank Act’s 2,300+ pages and 400+ mandates and rules are a number of clauses that seek to either introduce new, or change existing laws governing a broad spectrum of activity across America’s financial industry.

However, the points highlighted above are the key focus areas of The Act.

This publication seeks to give readers a high-level understanding of The Act, and describe (in the simplest terms possible) what The Act does, how it will be implemented, and what impact it is likely to have on America’s financial institutions.

All-in-One Change Management Tools

Top Rated Toolkit for Change Managers.

Get Your Change Management Tool Today...

IMPLEMENTATION MECHANICS

As can be imagined, any piece of legislation this complicated requires a great deal of planning, thought and effort to implement, and the 2,319 page Dodd Frank Act is no exception.

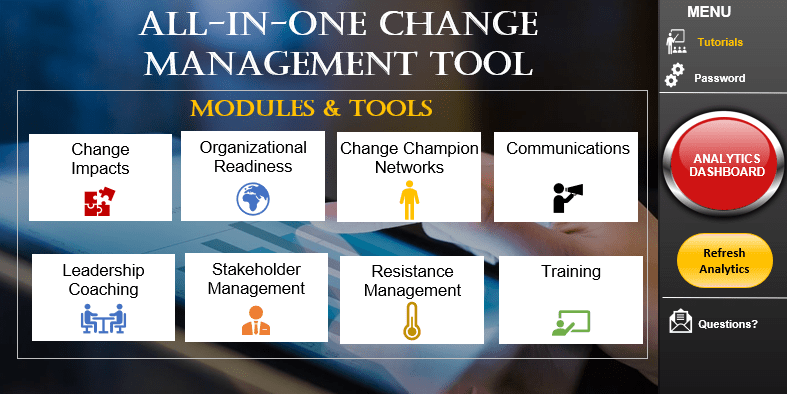

While some provisions of the Act (e.g., the Volcker Rule) was set to become law shortly after the Act became law, the following table lists the Estimates of Rulemaking By Agency that will be required before many other components are implemented.

Image Source: Estimates of Rulemaking By Agency

As can be seen from the rule-making estimates required, there are over 240 rules that are explicitly required for the Act to be fully implemented.

However, regulatory experts agree that, once the true law-making impact becomes clear, this figure is likely to more than double.

While The Act has laid out a regulatory framework for implementation, it has left the actual implementation mechanics in the hands of a number of existing agencies, including the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Reserve (the Fed), as well as newly-created agencies including the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

It is these bodies that will be involved in proposing, drafting, seeking approval, and ultimately implementing the slew of rules (new and updated) required.

The Dodd Frank Act implementation timeline presented above shows a high-level Gantt chart of the key rule-making, transition, and effective dates for each of the major components of the Act.

While it is estimated that full implementation will not happen until 2018, some experts believe that even that timeline is far too ambitious, and here’s why:

- The Act was conceived and approved in 2010, which is a “long time ago” when speaking in financial industry terms.

- Parts of the Act will come (and some have already come) on-stream in installments. As the intended targets (banks, hedge funds, credit rating agencies) of those provisions feel the full impact of those laws, they will likely modify their “behavior.”

- The impact of those modified behaviors could potentially trigger a review of parts of Dodd-Frank that have already been implemented, as well as those yet to be implemented.

- Such reviews inevitably result in legislative provisions either needing to be dropped, updated, or re-written altogether.

- If that happens, the 2018 target date might be pushed out further.

DODD-FRANK TITLES

The Act has been set out over 16 Titles, each dealing with specific aspects of the financial industry that need regulatory overhaul following the 2008 financial crisis. The following is a summary of each of the Titles:

Title I—Financial Stability—Systemic Risk Regulation and Oversight

The purpose of this Title is to establish a new structure for supervising inherent risk within the US financial industry. It also brings certain “non-banking” companies, which may be considered to pose significant threat to the economy, under regulatory scrutiny, and increases prudential standards required of a broad spectrum of financial institutions.

Title II—Orderly Liquidation Authority for Systemic Risk Companies

This Title specifically addresses concerns that the Fed had regarding their inability to deal with the contagion of risk events in 2008, which initiated from non-banking institutions. The Title now enables the Fed to place both banking and non-banking institutions into receivership under their (Fed’s) watchful eye, in case of a catastrophic event leading to the need to liquidate the company/corporation.

Title III—Transfer of OTS Authority to OCC, FDIC, Federal Reserve

Title III will see the elimination of The Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), and most of its responsibilities will be shared between three other Agencies, The Fed, the OCC in full (OCC), and FDIC in full (FDIC). FDIC deposit insurance levels for each depositor have also been increased, as has the minimum reserve ratio of the Deposit Insurance Fund.

Title IV—Regulation of Advisors to Hedge Funds and Others

Given that it was hedge funds that are primarily believed to have precipitated the financial crisis of 2008, Title IV seeks to regulate these companies more closely. It puts forward greater obligations onto advisors of private funds, as well as assumes the power to commission reports and studies into the private fund industry (or individual companies therein).

Title V—Insurance

A new entity, the Federal Insurance Office (FIO), has been created under Title V. The primary function of the FIO is to monitor and study the insurance industry, and compile reports and make recommendations to Congress regarding better/more effective regulation of the industry.

Title VI—Improvements to Regulation of Bank and Savings Association Holding Companies and Depository Institutions

The key aspect of Title VI is the “Volcker Rule,” which places stringent restrictions on the ability of certain financial entities to invest in hedge funds, conduct proprietary trading, or invest in private equity funds.

Title VII—Swaps and Derivatives Regulation (Wall Street Transparency and Accountability)

Through Title VII, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act (The Act) seeks to establish a fresh set of regulations for the over–the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets. Swap and derivatives dealers are now required to register with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC); derivative contracts will be subject to clearing and exchange processes; and the Fed/Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (i.e., taxpayers) are prohibited from providing insurance coverage to institutions engaged in swap transactions.

Title VIII—Payment, Clearing, and Settlement Supervision

Title VIII gives the Fed a broad range of discretion to determine (and mandate) additional regulations, supervision and oversight over payment, clearing and settlement systems.

Title IX—Investor Protections and Improvements to the Regulation of Securities

Title IX deals with a number of initiatives that enhance investor protection, enforces additional disclosures of asset-backed security transactions, and mandates greater reporting of executive compensation.

Title X—Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection

Title X creates a new Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (BCFP), which will have sole authority to propose/amend/enact a wide array of Federal consumer protection laws.

Title XI—Federal Reserve System Provisions (Lending Authority, Reserve Bank Governance)

Title XI reduces the number of situations in which the Fed can exercise its Emergency Lending Authority. It specifically stipulates that such lending (of taxpayer money) should only be provided in order to induce broad-based liquidity into the financial system, and enforces additional transparency into the Fed’s emergency lending activity, including audits by the Comptroller General, and greater access for the public (i.e., taxpayers) to information about the Fed’s lending practices.

Title XII—Improving Access to Mainstream Financial Institutions

Thanks to Title XII, here-to marginalized individuals and communities will now have greater participation in America’s financial environment by reducing the barriers that existed to such participation until now. This Title ensures greater access to mainstream financial products and services by low and moderate income earners.

Title XIII—Pay It Back Act

This Title reigns in Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) appropriations by the Treasury from $700B to $474B, increases the Treasury’s General Reserve Fund, and reduces its deficit. As a result, Title XIII now places more hurdles for government agencies to overcome before approving and using taxpayer money to bail out large, troubled entities.

Free Wealth & Finance Software - Get Yours Now ►

Title XIV—Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act

Title XIV seeks to address many of the ill-conceived mortgage and lending practices that lead to the 2008-09 housing bubble. Under this Title, predatory lending practices by lending companies are discontinued. In addition, lending companies are now mandated to ensure that they cease selling, to any consumer, any products/services that are too difficult (for the consumer) to understand. Explanations of product/service descriptions, risks, liabilities, and obligations must now also be provided (and explained) in “plain English” to consumers.

Title XV—Miscellaneous Provisions

Title XV covers a number of miscellaneous provisions, from restrictions placed on US funding of International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans to heavily indebted countries, to corporate involvement with Conflict Minerals, to additional health and safety reporting requirements for mine operators, to initiation of a number of studies that can have broad-reaching impact on US financial markets.

Title XVI —Section 1256 Contracts

This Title seeks to exclude certain types of swaps and securities contracts from preferential Internal Revenue Code (IRC) tax treatment. Under current Section 1256 provision, certain futures contracts can trigger 60% long-term and 40% short-term gains or losses when sold. This results in a favorable tax scenario for such contracts. This favorable treatment is revoked (for some contracts) under Title XVI.

AdvisoryHQ (AHQ) Disclaimer:

Reasonable efforts have been made by AdvisoryHQ to present accurate information, however all info is presented without warranty. Review AdvisoryHQ’s Terms for details. Also review each firm’s site for the most updated data, rates and info.

Note: Firms and products, including the one(s) reviewed above, may be AdvisoryHQ's affiliates. Click to view AdvisoryHQ's advertiser disclosures.